Tudor Rose Tapestries [TA2a-d]

Southern Netherlands, 1480s-1490s

Four tapestry fragments, wool and silk (the two larger pieces each approx. 258 x 155 cm; the two smaller pieces approx. 51 x 84 cm and 50 x 50 cm)

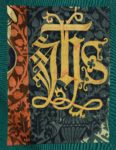

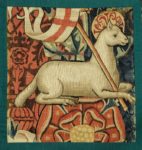

These four tapestry fragments were once part of single hanging. The two larger pieces, with heraldic devices, are on display in New Hall. Two smaller pieces, one bearing the IHS monogram and the other the Lamb and Flag, are in the College Archives.

The background of the tapestries imitates the effect of Italian damask, with a repeating vase and pomegranate pattern on vertical stripes of blue and red. Superimposed on this are the sacred monogram ‘IHS’, red and white Tudor roses, and a heraldic shield bearing three gold crowns on a blue ground.

The proliferation of red and white roses indicates a close association with Henry VII, the first Tudor king. They symbolise the union of Lancastrians (red roses) and Yorkists (white roses) through the marriage of Henry to Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV. The shields with the devices of three gold crowns were traditionally associated with the legendary King Arthur, namesake of Henry and Elizabeth’s eldest son, Prince Arthur.

Traditionally these fragments have been linked with Arthur’s baptism in Winchester Cathedral in 1486, though the art historian Thomas P. Campbell argues that they come from a set commissioned for Arthur in the late 1490s. This later dating, and the pomegranate device woven into the background, suggest a possible link with the betrothal of Arthur to Katherine of Aragon, whose badge the pomegranate was. An inventory of the belongings of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother, included ten pieces of ‘verdors with IHS the redde rose and the white.’ The Winchester fragments may well come from this set of tapestries.

It is not certain how they came into the College’s possession. In 1575 six tapestries were purchased by the College for the Chamber used by the Warden of New College on his regular visits to Winchester. An inventory made in 1582 lists ten pieces of tapestry in this room and early seventeenth-century inventories indicate that these included the Tudor Rose tapestry, along with the David and Abigail tapestries now in School. A 1604 inventory refers to one of the tapestries in the Warden of New College’s Chamber as a ‘peece of old Arras paned with crosses’. In 1619 it was a ‘large peece of Arras wrought with Roses and Crownes.’ These descriptions seem to indicate that the tapestry had not yet been divided. In 1685 the tapestries were moved to the Bursary, which was then in Exchequer Tower at the west end of College Hall. By 1846 they were in Audit Room, also in Exchequer Tower. They can be seen, now divided into separate pieces, in an illustration of the room published in Charles Radclyffe’s Memorials of Winchester College (1846). In 1903 the tapestries were cleaned and repaired, before being placed in glass frames. Since then they have been hung in various locations around the school (Musā, College Hall, Chapel), before being moved into New Hall as part of its refurbishment in 2014-15.

These fragments are among the earliest known examples of a type of heraldic hanging that would have been a regular part of the imagery of the Tudor court, but which rarely survive. Although the design was inspired by Italian fabrics, and the iconography is associated with the English crown, these pieces were almost certainly woven in the Netherlands, the centre of the late medieval tapestry industry.

Exhibited: Birmingham Art Gallery, July – August 1951 (Lamb of God only); Tournai, ‘Tapisseries héraldiques et de la vie quotidienne’, August – September 1970; The British Library, London, ‘Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination’, November 2011 – March 2012 (two tapestries – Lamb of God and one of the large pieces)

Literature: A. Kendrick, ‘Tapestry at Winchester College’, The Burlington Magazine, vol 6 (1904-5), pp. 490, 495; H. Chitty, The Winchester College Tapestries (Winchester, 1912); W.G. Thomson, Tapestry Weaving in England from the Earliest Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century (London, 1914), pp. 20-22; H. Chitty, Mediaeval Sculptures at Winchester College (Oxford, 1932), pp. 14-16; George Wingfield Digby, ‘English Tapestries at Birmingham’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 93, No. 582 (September 1951), p. 295; George Wingfield Digby, ‘Some Important English Tapestries Displayed at Birmingham in 1951’, The Connoisseur, Vol. 119 (Jan-June 1952), pp. 9-14; J.P. Asselberghs, ‘Les tapisseries tournaisiennes de la Guerre de Troie’, Revue Belge d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’Art, vol 39 (1970), pp. 93-182, no. 5; J.P. Asselberghs, Tapisseries héraldiques et de la vie quotidienne (Tournai, 1970), no. 5; Antony Emery, Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500: Volume III: Southern England (Cambridge, 2006), p. 425, n. 16; T. P. Campbell, Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, tapestries at the Tudor court (New Haven and London, 2007), pp. 80-82; R. Foster, Winchester College Treasury; a guide to the collections (Winchester, 2016), p. 9; J. Webster, ‘Rose Tapestries, 1480s’, in R. Foster (ed.), 50 Treasures from Winchester College (London, 2019), pp. 70-71.

Provenance: Uncertain, but probably acquired by the College in the late 16th century (see notes above); perhaps from a set once belonging Lady Margaret Beaufort (1441/3-1509); almost certainly originally commissioned for Henry VII.

Location: New Hall (the two large heraldic fragments), the two smaller pieces not on display