Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, late 14th century [MS15]

England

Manuscript on parchment, ff. 220. Bound in mid 20th-century alum-tawed pigskin over pasteboard by Roger Powell, with late 20th-century deerskin chemise by Tim Wiltshire (33.5 x 23.5 cm)

The Polychronicon was begun by Ranulf Higden (d. 1364), a Benedictine monk from Chester. His text became a staple compendium of world history framed within a biblical reference, but recounting secular events, specifically concerning the history of England.

Higden’s work survives in many copies from the 14th and 15th centuries, often with additions that bring the narrative up to date. This copy was owned and given to the College by its founder, William of Wykeham (1324–1404). It continues with events to the accession of Richard II in 1377, and it is therefore likely to have been written within a few years of the College’s foundation in 1382. The text is decorated with gilded initials, and the beginning of each of the seven books is marked with illuminated red and blue initials that extend into margins and frame the text. Near the end of book 1 (on fol. 51v) is a diagram of Noah’s Ark in red and black.

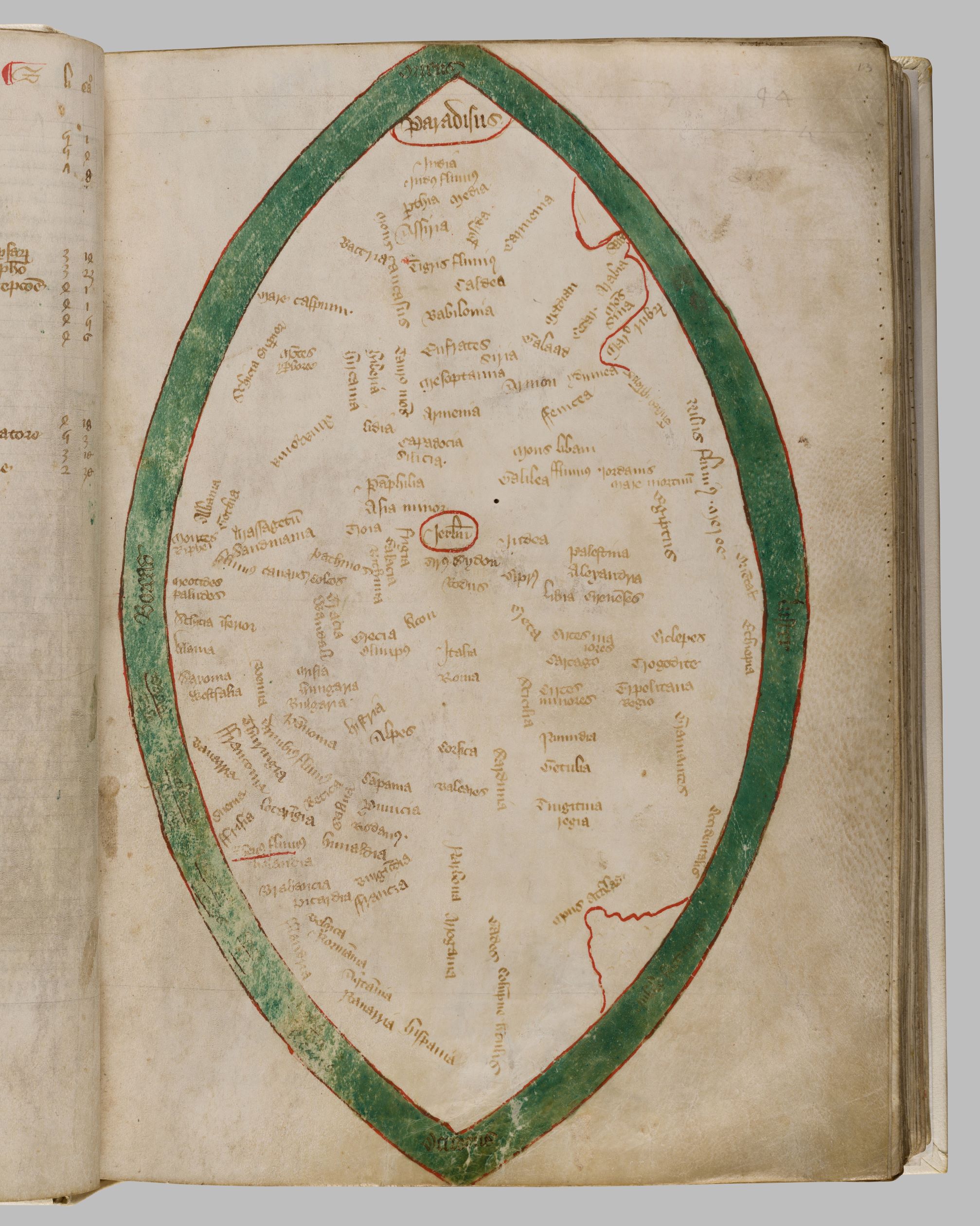

What gives this manuscript special significance is a map of the world drawn on the leaf immediately before the beginning of Higden’s text. Such maps are found in twenty-one copies of the Polychronicon, which together make up almost a quarter of the surviving medieval mappaemundi. Enclosed within a mandorla of bright sea-green are the places of the known world, broadly following the T-O division common in medieval world maps: placing Asia in the top half and Europe and Africa in the lower quadrants, left and right. Paradise is found in the East, the top of this map. Moving downward, Jerusalem is placed at the centre and the Pillars of Hercules in the West. In the bottom left is England, next to which the green sea has been partially rubbed away—perhaps by the fingers of its Winchester College readers over the centuries.

Literature: William H. Gunner, ‘Catalogue of books belonging to the college of St Mary, Winchester, in the reign of Henry VI’, Archaeological Journal, vol. xv (1858), pp. 1–16, 3-4, 12–14; Walter Oakeshott, ‘Some classical and medieval ideas in the Renaissance cosmology’, in Donald J. Gordon (ed.), Fritz Saxl, 1890–1948: a volume of memorial essays from his friends in England (London, 1957), pp. 245–60, 247–49; John Taylor, The Universal Chronicle of Ranulf Higden (Oxford, 1966), pp. 99, 107, 158, 178; Marcel Destombes, Mappemondes A.D .1200–1500: Catalogue prepare par la Commission des Cartes Anciennes de l’Union Giographique Internationale (Amsterdam, 1964); Neil R. Ker and Alan J. Piper, Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries, Volume IV: Paisley–York (Oxford, 1969), pp. 613–14; David Woodward, ‘Medieval Mappaemundi’, in John Brian Harley and David Woodward (eds), The History of Cartography, vol. 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean (Chicago, 1987), pp. 312–13, 364–65; Peter Barber, ‘The Evesham world map: A late medieval English view of god and the world’, Imago Mundi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography, vol. 47 (1995), pp. 13–33, 13–21; Ingrid Baumgärtner, ‘Graphische Gestalt und Signifikanz. Europa in den Weltkarten des Beatus von Liebana und des Ranulf Higden’, in Ingrid Baumgärtner and Hartmut Kugler (eds), BAND 10 Europa im Weltbild des Mittelalters (Berlin, 2009), pp. 81–132, 101–32; Churchill Babington (ed.), Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden, monachi Cestrensis, Together with the English Translations of John Trevisa and of an Unknown Writer of the Fifteenth Century, Vol. 1 (Cambridge, 2012), p. liii; James Freeman, The Manuscript Dissemination and Readership of the ‘Polychronicon’ of Ranulph Higden, c. 1330–c. 1500 (unpublished doctoral thesis, Cambridge University, 2013), p. 68 (no. 45), 69, 79 (no. 89), 90, 95 (no. 176), 126, 151 (no. 41), 159 (no. 79), 181 (no. 143), 184 (no. 156), 213, 322–23; James M. W. Willoughby, The Libraries of Collegiate Churches, Vol. 2 (London, 2013), pp. 599, 617, 632, 687; Liam Dunne, ‘Higden’s Polychronicon, late 14th century’, in Richard Foster (ed.), Fifty Treasures from Winchester College (London, 2019), pp. 48–49.

Provenance: Given to Winchester College by William of Wykeham before 1404.

Location: Fellows’ Library